In his book, The Culture of Ambiguity: Another History of Islam, the contemporary Islamic scholar Thomas Bauer wrote:

For about a thousand years Arab-Islamic societies cultivated a “culture of ambiguity.” Various truth claims were allowed to stand next to one another, and the search for the probable seemed to be satisfying enough. Only the colonialism practiced in the Middle East in the 19th century exerted pressure to define oneself through unique standards.[1]

Today, Islamism (or the political interpretation of Islam) strives for self-definition through demarcation, “... in a merely apparent reference back to traditional Islamic values.”[2]

Professor Dr. Dieter Dieterich in turn referred “... to the tolerant and very fruitful Islamic high culture in ‘Moorish Spain’ between 714 and 1492 and ... to the high esteem of Islam influenced by Sufism on behalf of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781), J.W. Goethe (1749-1832), Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866), and the Islamic scholar Annemarie Schimmel (1922-2003).”[3]

But does Islam really teach tolerance? How did Muslim rulers of the early Islamic period treat people of other faiths? How did Umar ibn al-Khattab, the second successor of the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon himafter Abu Bakr, deal with the year 638, when he encountered people of different faiths in villages inhabited predominantly by Christians? Is there any evidence that Umar tried to establish dialogue?

In this essay, I will examine the issue and concern myself with a place that could, today, be the place of a similar encounter between faiths – the Kathisma Church located between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. I will document the church’s history, and then study how the Muslims dealt with this Christian place of worship. In addition, I will try to clarify why the ruins of the church bear witness to the existence of a Muslim prayer niche.

Kathisma – a place of worship for both Christians and Muslims

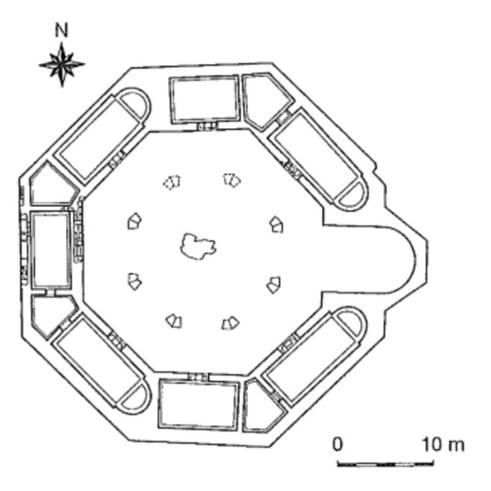

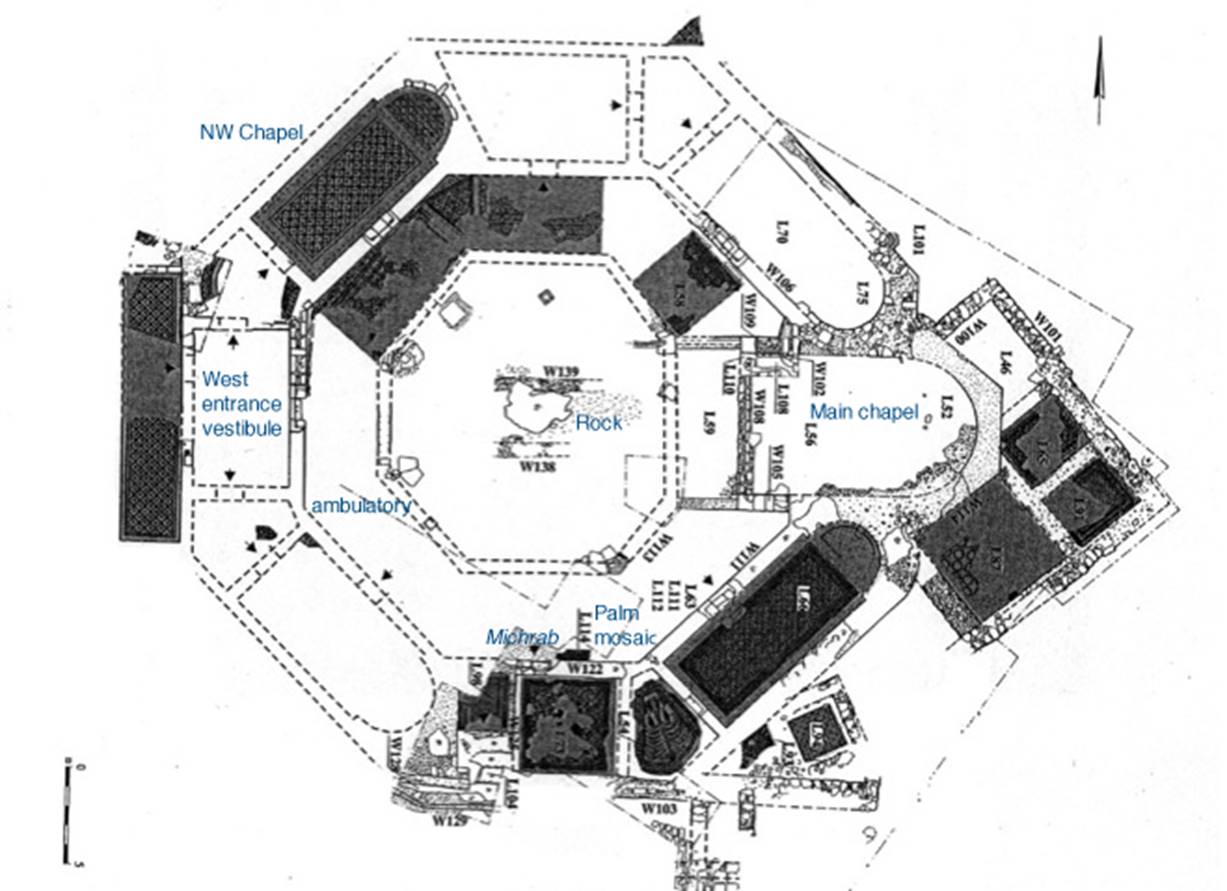

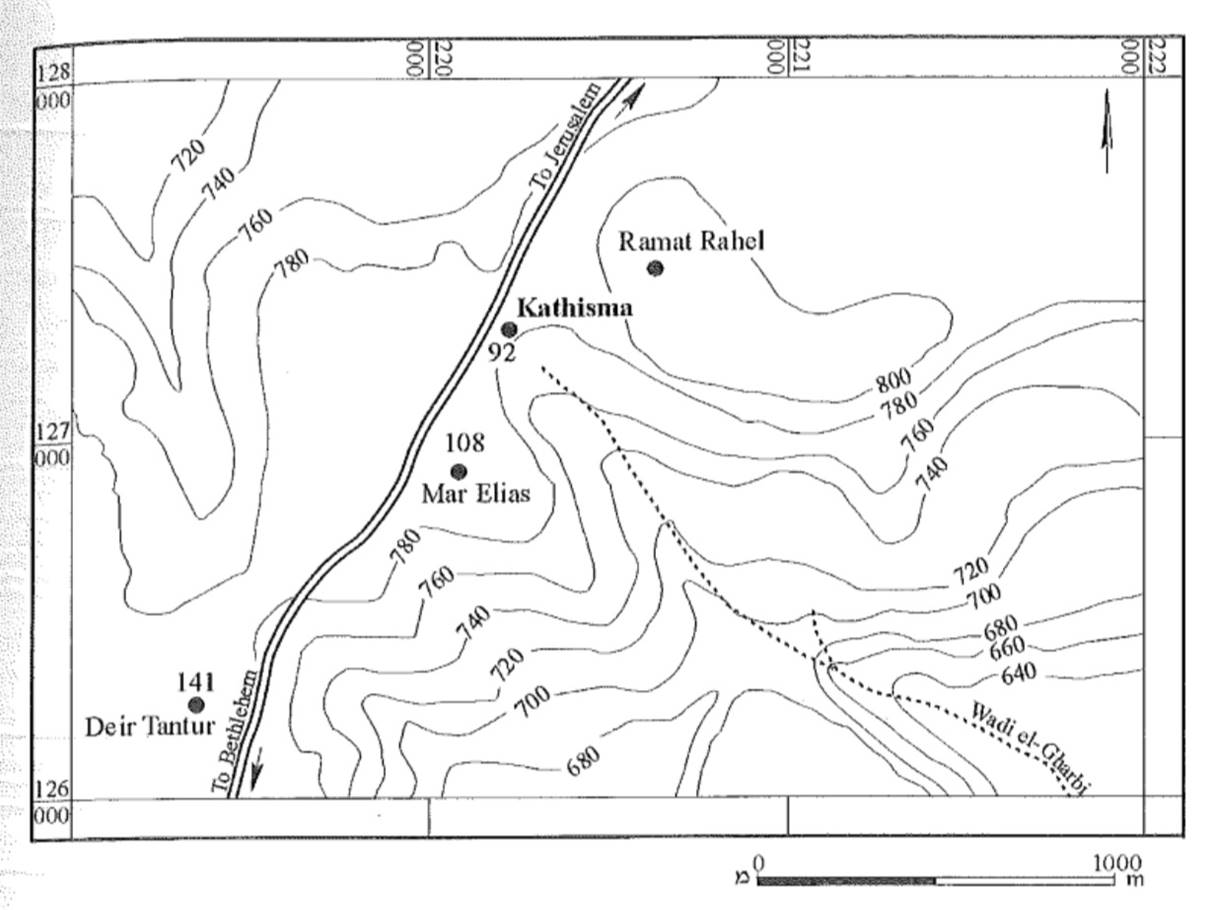

The Greek word “Kathisma” can be translated to mean “seating” or “rest area.” The Kathisma church, rediscovered in 1992 during excavations at the Kibbutz Ramat Rachel, halfway between Jerusalem and Bethlehem, is considered a model and a symbol for successful peaceful coexistence in early medieval times. In pre-Islamic times, the site is supposed to have served Christians on the pilgrimage from Jerusalem to Bethlehem as a rest area and a place of worship. It is alleged that the very pregnant Holy Mary herself rested on the rock over which this facility was built, when she made her way to Bethlehem. The church was in the form of an octagon, featuring the same scheme as the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. Figure 1 shows the octagonal shape of the building, with the apse aligned to the east, the rock in the middle and - added later - the Muslim prayer niche, the mihrab:

Figure 1: Kathisma-stone plan / floor plan, approximately 8th century [4]

Literary sources

a) The Gospel of James

In the so-called Gospel of James, an early Christian writing, which is believed to have been composed in the middle of the second century, there is an indication that on her way from Jerusalem to Bethlehem, Holy Mary stopped for a rest. However, there is only vague information provided, which also varies depending on the translation. In James 17:5-11, we read:

And he saddled his donkey and sat her on it and his son led and Samuel followed. And they arrived at the third mile and Joseph turned and saw that she was sad. And he said to himself, “Perhaps the child within her is troubling her.” And again Joseph turned around and saw her laughing and said to her, “Mary, what is with you? First your face appears happy and then sad?” And she said, “Joseph, it is because I see two people with my eyes, one crying and being afflicted, one rejoicing and being extremely happy.” When they came to the middle of the journey, Mary said to him, “Joseph, take me off the donkey; the child is pushing from within me to let him come out.” So he took her off the donkey and said to her, “Where will I take you and shelter you in your awkwardness? This area is a desert.”

b) A travel report by Archdeacon Theodosius

Another source noted that Mary may have rested at the place of the Kathisma church:

There is a place located three miles from the city of Jerusalem. When Mistress Mary, the Mother of the Lord, came to Bethlehem, she dismounted from the donkey, sat down on a rock and blessed it.[5]

This source, from the first half of the sixth century, at least adds to the extract from the Gospel of James the information that there was a rock Mary rested upon.

c) The pilgrim from Piacenze

In the 6th century, a pilgrim from Piacenze mentioned that the place had been blessed by Mary. He also said that a church was built there:

On the road to Bethlehem, at the third milestone from Jerusalem, the remains of Rachel are located on the outskirts of a village named Rama. Halfway off this road I saw motionless water pouring forth from a rock, and the people drew from this water, without it becoming more or less. Its flavor is indescribable; they say the reason for this is the fact that the Virgin Mary on her escape into Egypt took a seat there, thirsty; then this water was broken forth. There was also a church being built recently.[6]

Fig. 2: Map[7]

Archaeological finds

Archaeological finds and explorations on the spot indicate three construction phases:

First phase:

|

Construction and dating |

Ground plan |

Features |

|

First phase: 5th century |

Fig. 3 |

The church is built as an octagon, with a rock in the middle and an apse facing east. |

|

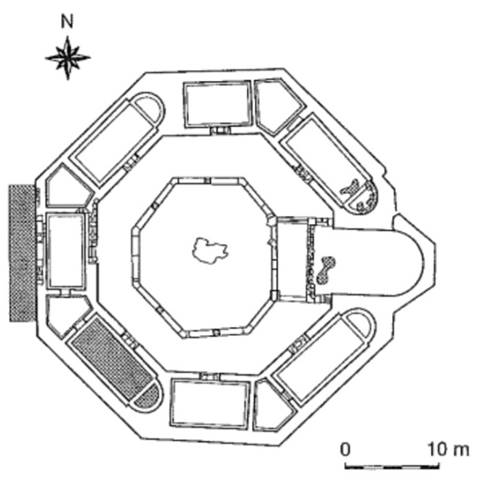

Second phase: 6th century |

Fig. 4 |

In the 6th century some enhancements have been made. But naturally, there is nothing yet that would remind you of a mihrab here. |

|

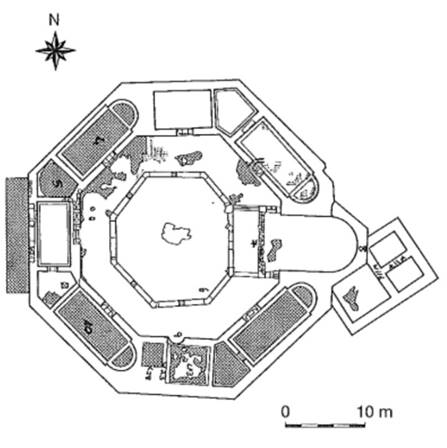

Third phase: First half of the 8th century |

|

Archaeological finds show that in the 8th century the place was used by both Christians and Muslims for worship. That means that the church was not destroyed by the Muslim rulers. |

One striking feature of these layouts (Fig. 3-5) is that obviously the Kathisma Church was supplemented by an Islamic prayer niche over time.[9] The fact that the prayer direction of the Muslims differs from the prayer direction of the Christians should have made it easier to carry out this modification. Even today, the remains of the mihrab are visible at the spot:

Fig. 6: Remains of the mihrab of the Kathisma Church[10]

![]()

![]()

Fig. 7: Remains of the mihrab and the rock[11]

Fig. 8: A photo of the remains from above[12]

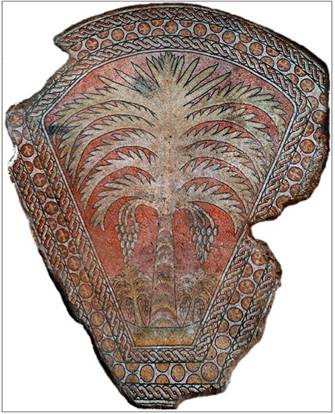

At this point, it should be noted that the Kathisma church remained undestroyed in the early Islamic period and was shared by Christians and Muslims. [13] This fits other evidence showing the two faiths co-existing peacefully. On a palm mosaic found nearby, it is evident that symbols were used which fit both religions:

Fig. 9: Kathisma-palm mosaic from the Arab period, Israel Antiquities Authorities

The palm motif is known to figure in both religions’ stories of Holy Mary. According to the Islamic tradition, she at least rested, but perhaps also brought forth her child under a (date) palm tree[14]; and it can be learned from apocryphal Christian stories that she refreshed herself by enjoying the juice and the fruits of a palm tree. [15]

The Kathisma Church in the 7th and 8th centuries

On the third ground plan (fig. 5) there is a prayer niche, which was probably added after the Arab conquest of Jerusalem and the surrounding area – an indication that Muslims and non-Muslims alike must have come to an agreement at that time to convert the Kathisma Church into a place of worship for both religions. The Arab expansion, which proceeded rapidly, especially after the death of the Prophet, reached Jerusalem and the surrounding villages in 638. In the annals of the historian Tabari, the text of a treaty has been handed down, which was concluded between the second caliph Umar and the Patriarch Sophronius:

In the name of God, the Most Merciful! The following is granted by Umar, servant of God and Commander of the Faithful, to the people of Aelia [Jerusalem] as a security guarantee: He has given them a guarantee for their lives, their possessions, their churches and crosses, for the sick and the healthy, and for the whole population [of the city].[16] Their churches are not to be destroyed or used for housing; neither the churches itself nor the associated property shall suffer any loss; nor their crosses or their other property. They shall not be affected in their religion, nobody is to suffer loss. [...] The people of Aelia are supposed to pay tribute as other cities do. [...] Those residents of Aelia who wish to leave with their belongings preferring to join the departing Byzantines and abandon their churches and crosses, shall be granted safe passage for themselves, their churches and crosses, until they are safe. [...] On this document are the guarantee of God and the protection of his envoy, and the caliphs and the protection of the faithful as long as they pay the tribute incumbent upon them. [Followed by the names of the witnesses.][17]

As shows, protection is granted both to all who want to stay in the city and to those who want to leave. Treaties of this kind were not unusual at that time. A contract had been concluded with the residents of Damascus as early as 635. The example of the Kathisma Church makes clear that Christian places of worship were protected and not destroyed. Last but not least, the preservation of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem testifies that the Muslim conquerors were wont to keep their promises.

Conclusion

The Kathisma Church can be understood as a clear sign of dialogue and coexistence – not only because it remained undestroyed under caliph Umar, but because it was used as a place of worship by both Christians and Muslims. A similar culturally ambiguous form of tolerance among people with different faiths and ways of thinking is still not evident today, which makes this sharing all the more impressive. Nevertheless, today there are similar projects, such as the House of One in Berlin,[18] the aim of which is to increase tolerance by providing information and conversations with people of different faiths (rather than merely about each other). Healthy understandings of dialogue and discourse are helpful in this regard.

Our example illustrates that as far back as the early period of Islam a peaceful coexistence between Christians and Muslims can be proven. Dialogue was, and still is, possible. Umar ibn al-Khattab’s reign as the caliph lasted from 634 to 644. More examples could be cited from this period that confirm his willingness to engage in dialogue with people of other faiths and ways of thinking. Historical testimonies bear out, for example, the right for residence to the Jews of Jerusalem, granted after 500 long years of persecution.[19] In-depth research on this period and subject shall bring other instances to light.

[1] Bauer, Thomas; Die Kultur der Ambiguität. Eine andere Geschichte des Islams; Berlin 2011, blurb.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Dieterich, Dieter: „Ungewohntes bringt uns weiter. Für eine Kultur der „Ambiguität“, in: Das Gespräch aus der Ferne. Vierteljahreshefte zu wesentlichen Lebensfragen unserer Zeit. Nr. 403. II/2013. Vol. 66, p. 20

[4] Vergleiche: Avner, Rina; “The Recovery of the Kathisma Church and its Influence on Octagonal Buildings,” in: Bottini, Giovanni Claudio/Segni, Leah Di/Chrupcala, Leslaw Daniel (Ed.): One land – Many Cultures. Archaeological Studies in Honour of Stanislao Loffreda; Jerusalem 2003, p. 177, fig. 4.

[5] Archidiakon Theodosius; Theodosii de situ terrae sanctae, emerged about 530 AD.

[6] Latin version in: Antoninus <Placentinus>; Itinerarium Antonini Placentini. Un viaggio in Terra Santa del 560 – 570 d. C.; Mailand 1977, p. 178f.

[7] Avner, Rina: “The Initial Tradition of the Theotokos at the Kathisma: Earliest Celebrations and the Calender”, in: Brubaker, Leslie/Cunningham & Mary B. (Hrsg.); The cult of the Mother of God in Byzantium. Texts and Images; Farnham 2011, p. 11, fig. 1.1

[8] Fig. 3-5 taken from: Avner, Rina: “The Recovery of the Kathisma Church and its Influence on Octagonal Buildings”, in: Bottini/Segni/Chrupcala; One Land – Many Cultures; p. 177

[9] See Avner: “The Recovery”, S. 173-186 or Andonia, Beata; “Kathisma - Place of Rest on the Way to Bethlehem”, in: http://www.travelujah.com/blogs/entry/Kathisma-Place-of-Rest-on-the-Way-to-Bethlehem, as of 02.20.2015.

[10] Photo from 09.25.2013

[11] Photo from 09.25.2013

[12] Photo from 09.25.2013: Israel Tours: Kathisma Church, 05.12.2011, in: https://israeltours.files.wordpress.com/2011/12/kathisma-aerial.jpg, as of 02.20.2015

[13] See Cornell, Vincent J.; “The Ethiopian's Dilemma: Islam, Religious Boundaries and the Identity of God”, in: Jacob Neusner/Baruch A. Levine/Bruce D. Chilton/Vincent J. Cornell (Ed.): Do Jews, Christians, and Muslims Worship the Same God?; Nashville 2012. S. 95-98; see Avner, Rina: “The Dome of the Rock in Light of the Development of Concentric Martyria,” in: Jerusalem: Architecture and Architectural Iconographie, Muqarnas 27, 2010, p. 31-49

[14] The Qur’an, 19:23-36

[15] See Avner: “The Dome”, p. 37-42; see Cornell: “The Ethiopian's Dilemma”, p. 97-98

[16] Accentuations made by the author

[17] From the Annals of Tabari, quoted from: Halm, Heinz: Der Islam, 2011, p. 26f., abridged version

[18] Website of “The House of One”, http://house-of-one.org/de

[19] Tilly, Michael: „Jerusalem von der Spätantike bis zur Gründung Israels. Unter fremder Herrschaft“, in: Damals. Das Magazin für Geschichte. Das jüdische Jerusalem, in http://www.damals.de/de/16/Unter-fremder-Herrschaft.html?issue=134759&aid=134746&cp=1&action=showDetails, as of 01.28.2015.